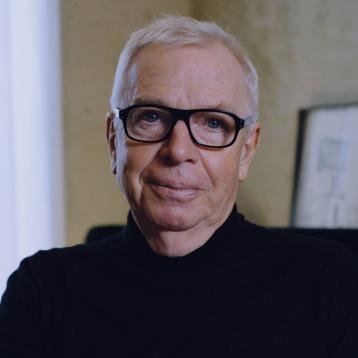

Sir David Chipperfield

Sir David Alan Chipperfield CH.

Photography: Tom Welsh

A foreign architect

David Chipperfield Architects, London, United Kingdom

This story was originally published in Indesign Magazine Issue #22 in 2005, and has been reproduced here to mark Sir David Chipperfield’s receipt of the Pritzker Prize in 2023.

David Chipperfield Architects is currently working on projects in London, Glasgow and Wakefield in the UK, Barcelona, Berlin, Milan and Venice in Europe, and Anchorage, Des Moines and Davenport in the USA. The firm’s globetrotting principal touched down in Australia for one week in March, and told Rachael Bernstone about his approach to architecture in far-flung places.

David Chipperfield’s work has been variously described as ‘minimalist’ and ‘modernist innovation’, but the architect himself would rather call it reductionist. “Minimalism has come to mean many different things: I don’t think I would choose minimalism to describe my own work,” he says. “We like to reduce architecture down to quite elemental parts, we don’t like putting too much stuff in our buildings. We like to reducing the palette of materials and form, and to some degree ideas, as well. That’s a different strategy to minimalism.”

While his firm’s list of completed and current projects reads like the index of an atlas, all of the work displays a common thread, which Chipperfield describes as “an underlying series of attitudes”, rather than a design motif or theme that might link the work of an architect whose output is contained in one geographical area.

“I’m more interested in normality than the extraordinary, and I think of architecture as a sort of background or framework,” he explains. “There are times when architecture has to work hard to seek attention and bring notice to itself in a formal way, but I take another approach.

The Neues Museum 2009, Berlin, Germany.

Photography: Courtesy of SPK / David Chipperfield Architects, photo Joerg von Bruchhausen

“In its normal role, architecture creates a framework for things to go on inside,” Chipperfield continues. “That framework should be stimulating: I don’t think it should be neutral. It can be quite evocative, but I don’t think it should occupy the centre of our concerns, rather, it should be an a environment in which the ritual of daily life can be played out.”

While working in vastly different locations poses particular challenges, it also provides certain benefits, Chipperfield says.

“We are trying to find a way to respond to very different building types and locations, and we tackle different issues with every project,” he says. “However, issues of context are sometimes easier when you don’t live in a place. It’s often easier to develop an opinion about something when you step in from the outside. There’s some advantage to not being ‘of’ a place as well, in the sense that there’s a certain freedom of expression when you are invited to do something in another city.”

These two factors – seeing architecture as a frame, and feeling comfortable working in foreign places – go some way to explaining the firm’s success in winning international architectural competitions, which is how it comes by most of its new projects.

The Neues Museum, 2009, Berlin, Germany. Photography: Courtesy of Ute Zscarnt for David Chipperfield Architects

The Neues Museum 2009, Berlin, Germany. Photography: Courtesy of SMB / Ute Zscharnt for David Chipperfield Architects

In 1997, DCA won the competition to restore Berlin’s Neues Museum, which was designed by Friedrich August Stüler between 1843 and 1855, and partially destroyed by bombing in World War II. It stood as a ruin for 60 years. Rather than faithfully filling in the holes created by the bombing, or building a new wing to contrast with the original, Chipperfield opted to restore the form without the ornament.

“The damage is very erratic,” he said. “There’s some parts of the building that still have architectural and decorative details, and other parts are missing completely.

“Should we include the passage of time as part of [the building’s] meaning?” he asked. “The ruin is so powerful, and 60 years seemed to be such a significant proportion of the building’s life, that I thought you couldn’t sweep it under the carpet.

“To me, the building is like a broken, wounded animal, and we want to give it back its dignity,” he added. “If you just fill in the gaps, people would have no idea what was original and what was new.”

The painstaking process has involved careful cataloguing of the entire building in its current state, and then building up the individual layers in each room, before deciding on a point in the restoration. In the main entrance hall, for example, that will involve restoration of the stair itself, with a plain colour wash where the decorative friezes used to be.

“It’s fundamental to this process to restore the volumes and spaces, but we are not interested in imitating the decorative surfaces,” he said. “The best metaphor for what we are doing is the restoration of a Greek vase,” he adds. “The fragments on the table don’t mean much, but when you put them back together and fill in the blanks, you give them significance back to the whole without copying the detail.”

The project, which is budgeted to cost more than 230 million euros, is due for completion after 2012, making it a 15-year job, and one that Chipperfield said was the “most fascinating project we’ve ever done”, and clearly demonstrated the benefits of being a foreign architect.

“We couldn’t have taken this approach as German architects,” he said. “It’s easier for me to say it and it’s easier for them to accept this way. It brings up questions such as ‘How you operate outside of your own culture?’, and ‘What right do you have to turn up and tell them how to do things?’

River And Rowing Museum 1997, Henley-on-Thames, United Kingdom. Photography: Courtesy of Richard Bryant / Arcaid

In the UK, architecture is dominated by pragmatism, if a design is going to save money or be faster, it will win out, whereas in Germany, it’s all about the ideas.”

That might explain why Chipperfield hasn’t built many projects in his home country, although his River and Rowing Museum at Henley on Thames, completed in 1997, is highly regarded. It won several professional awards, and praise from modern architecture’s harshest critic in the UK, Prince Charles.

Another museum overlooking a river is the firm’s current project to build the Figge Museum in Davenport, Ohio on the banks of the Mississippi. Chipperfield said that the city had lost its connection to the river, as a result of surface parking all over the city centre.

“The city desperately wanted a ‘downtown’, and being in the mid-west, the museum is very serious about education,” he explained. “Bearing all that in mind, we created a building that was visible from afar, which regains its relationship with the river. The horizontal volume has a special room on top to allow visitors to appreciate the view. There’s nowhere else in the city where you can view river from, apart from coming down to river itself.”

The Des Moines Library in Iowa will fulfil a similarly important civic role, through its location in the city’s Gateway Park. “There’s a huge concern in America about public libraries at the moment, because no one is visiting them,” he said. “And its not because people aren’t interested in books: you only have to look at Barnes & Noble and Borders to see that. We’ve therefore created a building that enjoys its situation in the park, but also, you have to go through the building in order to access the park.”

It will be clad in copper mesh to provide protection from the sun while still offering good views of the park, in what Chipperfield calls a “play on transparency and solidity”.

Chipperfield acknowledges that all of these international projects require a different way of working than if he was to concentrate on local jobs.

“If you are working in Mexico, it’s possible to get something very beautiful, look at the work of [Luis] Barragan and [Ricardo[ Legoretto,” he said. “If you compare it to a project in Switzerland, it might look crude in terms of craftsmanship, but on the other hand, you are likely to achieve something you wouldn’t get in Switzerland.

“It goes without saying, therefore, that what works in London may not work anywhere else, and you cannot control large projects through conventional methods,” he concludes. “It’s possible to do a little house and slave over the details, but on bigger projects, modifications have to be made: the budgets have changed and it’s important to develop physical ideas that don’t depend on the level of craftsmanship in construction or architecture that you might employ on smaller projects.

“For example, at a conceptual level, you might have anticipated how something might be realised: clearly Carlo Scarpa knew how he wanted things to look, even though he relied on architecture being part of an interpretive process,” he said. “Now you control a project down the telephone line, so you have to be clear about everything, so that your intentions can’t be misinterpreted.”

River and Rowing Museum 1997, Henley-on-Thames, United Kingdom. Photography: Courtesy of Richard Bryant / Arcaid

Consequently, Chipperfield says, he would rarely use timber in a large, international project. “I’d be very nervous about using wood in any way that was not really ruthlessly explicit: it’s much easier to specify glass,” he says. “We stay away from certain ways of doing things on certain projects that we might be attuned to in other projects. It’s not just an issue in craftsmanship: it becomes part of the conceptual process.”

His own house in Galicia, Spain exemplifies his exceptional ability to fit in with the context of a place while at the same time producing an architecture unlike anything else there.

“The house is on the Atlantic coast, and it overlooks the very strong sea and a fantastic port, and the fishing village is still occupied by fishermen,” he says. “The site was like a missing tooth in a string of ugly buildings. It appears that these fisherman aren’t interested in looking at the sea when they come home, so there’s not many windows in the houses.

“The question in this case was ‘How do we put create a building without rejecting what’s there?’ or how can we be a part of it and sit away from it at the same time?”

The resulting strategy follows the line and geometry of existing buildings, where neighbouring houses are three and five storeys high, and the windows are small.

“We’ve deliberately got different angles to reflect the houses either side, and different sized window panes, to relate back to the other small windows in the seafront,” he said. “As a result, our house fits in, but creates something different at the same time.”

The same could be said of all of Chipperfield’s projects, regardless of where they are and who the client was. Which begs the question, what concerns would this foreigner address if he was to tackle a commission in Australia?

The Neues Museum 2009, Berlin, Germany. Photography: Courtesy of Ute Zscharnt for David Chipperfield Architects